The Swiss Cheese Model of AI

For the entire history of the software industry, we have been building tools to make people better at their jobs. Software has touched every profession, from accounting to architecture to art, with immeasurable economic and productivity gains.

With the advent of generative AI technologies like LLMs and Diffusion models, we are now moving beyond selling tools to selling outcomes. AI products don’t just promise to make people better at their jobs, they promise to do those jobs. It’s a massive shift.

Such a shift in value demands a shift in business models. Software-as-a-service was a vast improvement over the on-prem and installed software business models, allowing companies to rent software as needed. Buying software became faster and easier, accelerating adoption.

AI, with its radically new value proposition, needs a similar leap forward in business models. Companies cannot buy AI products the same way as traditional subscription software, as it’s hard to test them quickly and even harder to manage adoption. AI tools are complex, and the outcomes they complete can take time, requiring a very different approach.

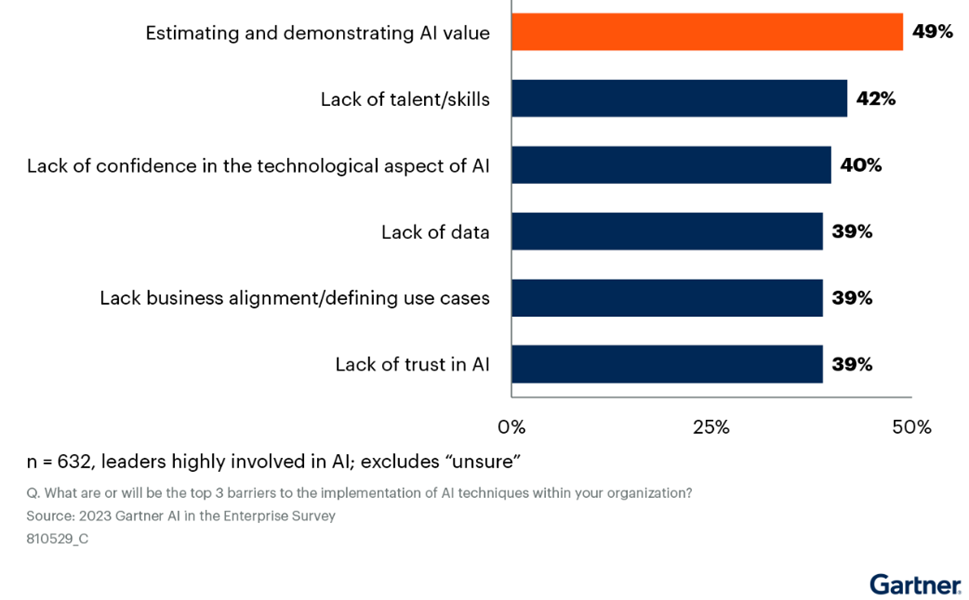

You can see this in the barriers to AI adoption, where enterprises want to start using AI tools but are having trouble doing so:

AI needs a business model that allows companies to try before they buy, without requiring massive upfront investment and payback periods measured in years.

We see the early signs of that model in Services With Integrated Software (SWIS). This is a simple concept where the customer buys outcomes instead of subscriptions. As with consulting, the customer hires the AI company to produce an outcome, and it’s up to the company to produce the outcome. They might use humans, they might use AI, or a combination of the two.

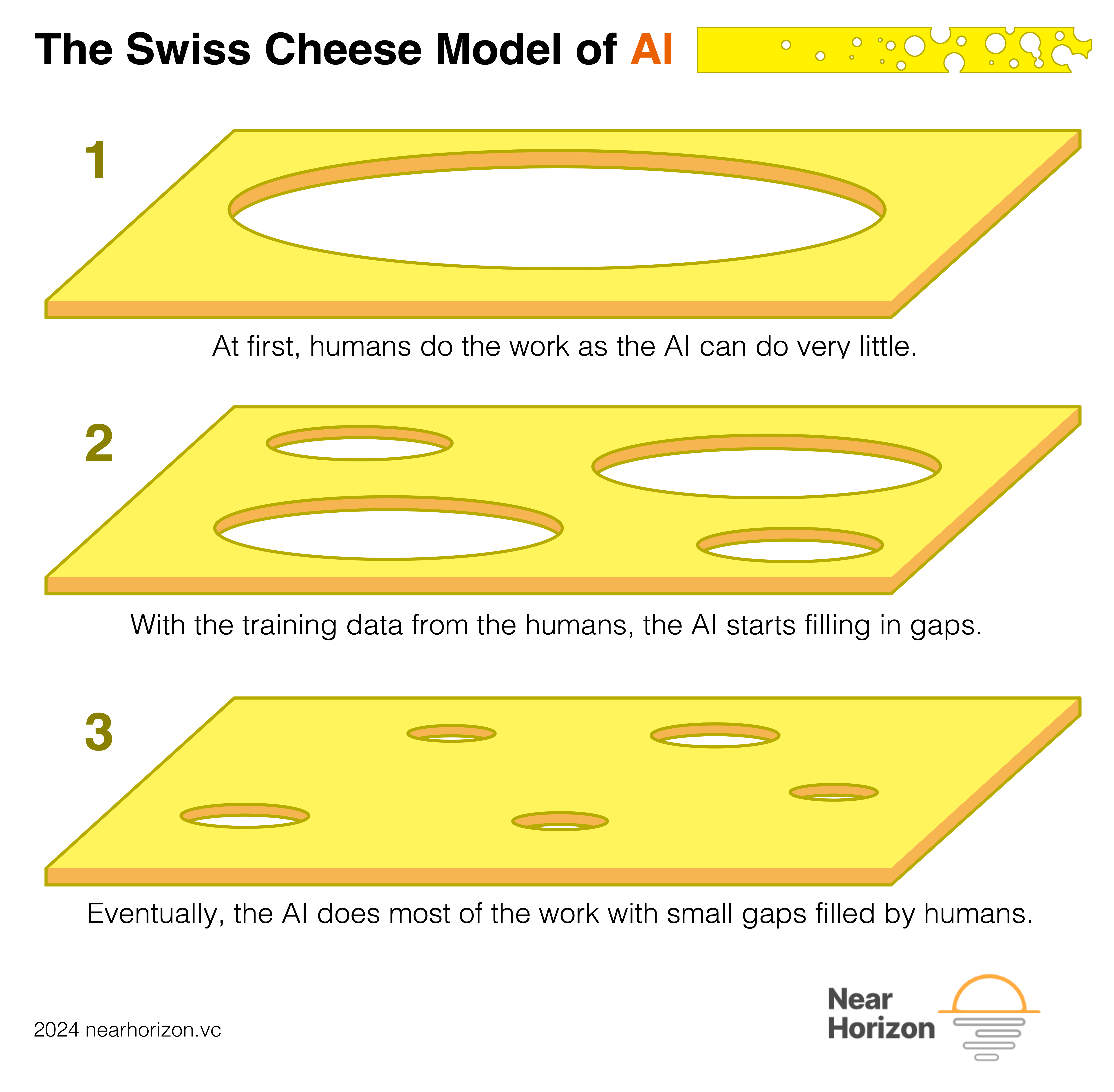

This model first arose with the first wave of AI companies a decade ago. Building AI products is hard, and the first versions rarely meet all the needs of the customer. By selling the product as a consulting engagement with a specified outcome, the company can be the primary user of the AI product and see where the gaps exist. Then, they can manually fill in the gaps while working to build out those same gaps in the product. After enough time and enough engagements, the AI product will be developed to where it’s self-sufficient.

For example, let’s say you are starting a new AI company to do accounting for large companies. It would take years for you to match the feature set of NetSuite, and that is before you even start to build the AI features! Or, you can hire some accountants today and start selling immediately.

At first, those human accountants would do 100% of the work while you build the AI systems trained on the work of the humans. Over time the human accountants will do less and less of the work as your AI system does more and more. Eventually, human accountants will simply audit the work of the AI accounting system, just like supervisors look over the work of junior employees.

The beauty of this model is that it allows AI companies to start selling quickly, while removing the risk for the buyers. The buyers get guaranteed outcomes and the AI companies get a chance to improve their product with real world problems. Everyone wins.

The only downside of this model is that the margins for SWIS businesses start slim. For the first customer engagements, the work performed by humans is expensive. However, margins improve as the software improves, and eventually match or exceed those of traditional software companies as the humans are taken out of the loop.

While this does mean AI companies are more capital intensive to launch than traditional software companies, the early indications are that they can charge substantially more. Customers are willing to pay more for outcomes than for tools, and that makes AI products more valuable.

We are optimistic that the SWIS model will prove to be the best for AI-driven companies, especially in their early days, and the early indications are promising.